Protecting the UK’s critical national infrastructure

The UK’s critical national infrastructure (CNI) consists of the most important systems in the country – responsible for keeping the economy functioning and supplying services to homes and businesses.

Historically CNI was focused on physical assets, such as buildings, housing, energy and infrastructure. They tend to change infrequently, as moving infrastructure to an entirely new industrial estate didn’t happen often.

However, the pace of change accelerated, and the UK is now more dependent on digital infrastructure. The systems underpinning communications, financial networks, and the internet change more rapidly and are often highly distributed.

Recent changes in the geopolitical environment, including the ongoing war in Ukraine, the rise of state-aligned groups around the globe and an increase in aggressive cyber activity, means the threat status for the UK’s CNI has heightened.

The 13 critical national infrastructure sectors

CNI includes organisations that provide safe drinking water, electricity, the internet, health and emergency services, as well as the government itself.

The UK government’s official definition of CNI is:

“Those critical elements of infrastructure (namely assets, facilities, systems, networks or processes and the essential workers that operate and facilitate them), the loss or compromise of which could result in:

a) Major detrimental impact on the availability, integrity or delivery of essential services – including those services whose integrity, if compromised, could result in significant loss of life or casualties – taking into account significant economic or social impacts; and/or

b) Significant impact on national security, national defence, or the functioning of the state.”

In the UK, there are 13 national infrastructure sectors:

- Chemicals

- Civil Nuclear

- Communications

- Defence

- Emergency Services

- Energy

- Finance

- Food

- Government

- Health

- Space

- Transport

- Water

According to the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), ransomware remains one of the greatest cyber threats to the UK’s CNI sectors.

This has been demonstrated clearly in the past 12 months with attacks against Colonial Pipeline, the Irish Health Executive, South Staffordshire Water, Royal Mail International and even one which impacted NHS 111.

Some of the attacks also highlighted vulnerabilities outside of the CNI itself, targeting key suppliers who may have potentially weaker security and therefore providing an attractive “way in” for cyber-criminal gangs.

In May 2023, NCSC issued a joint advisory alongside agencies from the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, revealing details of “Snake”, a sophisticated espionage malware used by Russian cyber actors.

These targets included CNI operators in more than 50 countries globally. The “Snake” implant is considered the most sophisticated cyber espionage tool designed and used by Center 16 of Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) for long-term intelligence collection on sensitive targets.

According to the advisory: “Globally, the FSB has used Snake to collect sensitive intelligence from high-priority targets, such as government networks, research facilities, and journalists.”

NCSC CEO Lindy Cameron, (pictured above) said: “The last year has seen a significant evolution in the cyber threat to the UK – not least because of Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine but also from the availability and capability of emerging tech.”

Prioritising cyber security

To make sure that the NCSC continues to focus its work where it is most needed, and to deliver against the objectives in the government’s National Cyber Strategy, it will focus on three priorities over the coming year:

- improving the UK’s cyber resilience;

- retaining its edge;

- being the strongest organisation it can be.

Much of the UK’s CNI is operated by either public or private sector organisations and, while they are subject to the threats detailed above, they also face a range of other commercial pressures.

This means protection against and tackling existing, cyber threats are not always prioritised as highly as NCSC would like.

Operators of the UK’s CNI may be positioned to deliver shareholder value and profit, incentives that can take priority over investment in the secure operation of critical systems.

Firms with less mature security can also be incentivised to constrain information sharing during incidents, limiting the NCSC’s ability to effectively support and respond.

The public sector, whilst not motivated by profit, prioritises the delivery of these critical services, but unfortunately, this can also come at the expense of security considerations.

NCSC has been working with government, industry, and regulators to address this imbalance.

The government has set targets for CNI operators to achieve resilience against common attack methods as quickly as possible and to put in place more advanced protections where appropriate.

Effective regulation plays a key role, so the government is also strengthening the regulatory framework, to improve its coverage, powers, and agility to adapt, within the context of broader national security risk and rapidly changing threat and technology.

While the cyber activity against the UK’s CNI often focuses on DDoS attacks, website defacements and/or the spread of misinformation, some cyber groups operating in this sphere have stated a desire to achieve a more disruptive and destructive impact according to the NCSC’s latest annual review.

Without external assistance, NCSC considers it unlikely that these groups have the capability to deliberately cause a destructive, rather than disruptive, impact in the short term.

But they may become more effective over time.

What should we do next?

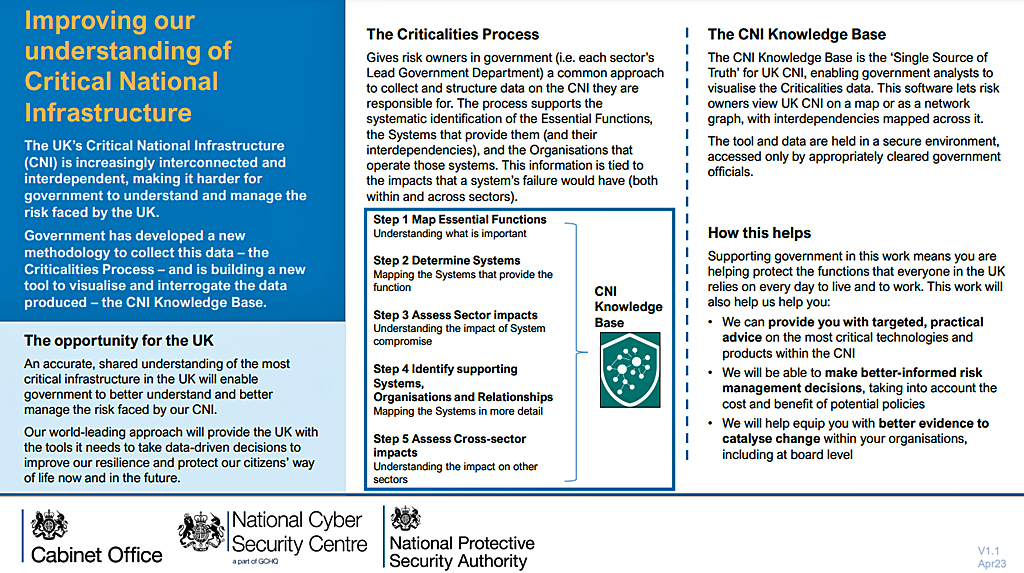

The NCSC has worked to address these challenges by supporting the creation of a revised criticalities process to identify and assess critical systems across the UK.

In addition, it has helped create the Knowledge Base, a world-leading tool which permits the government to understand the relationships between and impact of any disruption to critical systems, regardless of the hazard involved.

The CNI Knowledge Base software lets risk owners view UK CNI on a map or as a network graph, with interdependencies mapped across it. The tool and data are held in a secure environment, accessed only by appropriately cleared government officials.

NCSC is continuing to work together to address the gaps in the UK’s cyber security, starting with gathering better data to improve visibility and better inform decision making.

It is seeking to understand where organisations commonly struggle to address security challenges and how adversaries are attempting to exploit those vulnerabilities.

In collaboration with industry, wider government and regulatory bodies, NCSC is analysing data on the cyber resilience of the UK’s CNI to better understand how it can remain secure.

Working with other countries, the UK is forging partnerships to ensure it can learn from and work with other governments, industries and relevant forums overseas on this shared challenge.

Similarities between each country’s CNI means similar threats and working together to create a common toolkit for managing them is key.

Veracity Web Threat Protection

Making your business safe shouldn’t take more time and money than you can afford, which is why Veracity Web Threat Protection only requires a single script, and doesn’t interfere with existing DDoS or WAF solutions.

We want to get this technology to as many people as possible — as easily as possible. At Veracity, we’re specialists in bot detection and attack prevention, it’s not simply an add-on.

Want to see what we can do?